The New European Sustainability Reporting Space

Corporate sustainability reporting is rapidly evolving worldwide. Previously relying on a wide range of industry-led reporting systems, standardization is now becoming a reality, especially in the European Union (EU).

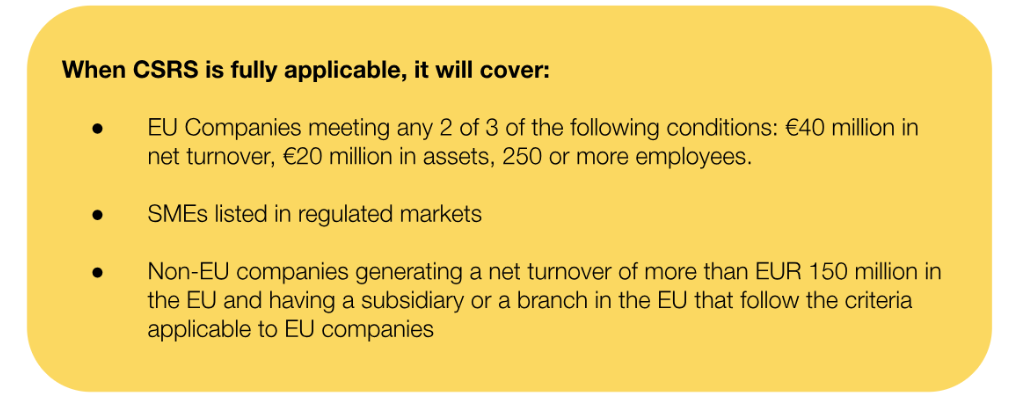

An important milestone was achieved earlier this year, when the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) entered into force. Large public interest companies will be required to report on their 2024 ESG metrics and provide data in a machine readable format (XHTML) to the European Single Access Point (ESAP). Progressively until 2028, more companies will be required to report, including non-EU companies operating in the European market.

Within this space, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) provide an official comprehensive framework for sustainability reporting. However, when an impact, risk or opportunity is not sufficiently covered within the standard, businesses may need to use additional sector-specific or even develop entity-specific disclosures.

Disclosures comprise quantitative and qualitative data on environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters, covering short, medium, and long-term horizons and the company’s entire value chain. Assurance of ESG data will be provided by statutory auditors (legally required) or an accredited third party. Currently the standard is limited assurance, but in the future, reasonable assurance may be required, a more rigorous level now used for financial data.

What sustainability aspects should the drone industry consider?

Most drone industry organizations are not directly affected by CSRD because they do not reach the size thresholds for mandatory reporting. However, the drone industry, like any other, will have to incorporate sustainability strategies to operate in increasingly sustainability-sensitive markets, in the EU and elsewhere.

In a relatively emergent industry like drones, sustainability frameworks and the associated metrics, adequate policies, actions and targets are not as consolidated as for more mature industries like textiles, agriculture, oil or gas. There is still a lack of sectoral standards on drones’ sustainability, but progress is being made in related fields. For example, sectoral standards for motor vehicles are under development within the European CSRD framework.

Prior to reporting, drone businesses have to look at their direct sustainability impacts and risks. Probably the first environmental (E) issue that comes to mind is the manufacturing of drones and their waste disposal. This is indeed important and not much different from other electronic industries. Technical expertise and engineering solutions together may result in procedures that integrate these matters to make the product management process as clean as possible.

Drones business will also have to consider the social (S) impact of their activities towards their own workforce or workers in the value chain. Similarly, from a governance point of view (G), drone business should consider business conduct.

Drones business will also have to consider the social (S) impact of their activities towards their own workforce or workers in the value chain. Similarly, from a governance point of view (G), drone business should consider business conduct.

Nevertheless, the most relevant sustainability matters for drone businesses will be specific to the type of activities that a company is engaged in. These relevant environmental, social and governance matters will be deemed material using sustainability jargon. The challenge is that assessing materiality is not always as straightforward as it seems.

How does a drone company know what issues are most relevant for its reporting?

A materiality assessment is a critical process that helps companies identify and prioritize the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues most relevant to their business and related stakeholders. Incorporating human-centered design principles, this assessment ensures the company's sustainability reports focus on significant impacts and risks, aligning with regulatory requirements and stakeholder expectations. By engaging with internal and external stakeholders, companies can determine which ESG topics are material, enhancing transparency, accountability, and strategic decision-making for risk management and impact enhancement. Ultimately, a robust materiality assessment fosters trust and drives long-term value creation.

Material topics for drone business may comprise topics such as privacy, noise, safety, fear, misconceptions, and other issues affecting communities. For example, for companies providing drone services for agriculture, privacy and noise won’t be relevant matters, but noise and privacy will be of utmost materiality for a drone company transporting medical supplies in urban areas.

Additionally, drone businesses should consider indirect sustainability implications. The most common is that drone businesses may be required to provide data to larger client companies that buy drones or use drone services to include the drone company ESG data in their sustainability reports. For example, the GHG emissions of a drone service provider may need to be accounted for as part of the upstream emissions of a large company (referred to as scope 3 emissions).

Drones may also be used as tools for the sustainability strategy of a larger company. For example, electric drones may be used as a mitigation tool to reduce overall GHG emissions for large companies. Similarly, drones can improve safety conditions for workers inspecting infrastructure in hazardous environments, such as heights or hard to reach locations.

How can drone businesses put sustainability matters into practice?

Figure 1. Noise map of the flight path across lake Geneva and at landing generated with SAFTu

Recently we worked with Rigi Tech to identify and mitigate material community impact of their drone delivery across Geneva lake. In this project, one the most relevant material aspects was drone noise, which we helped Rigi understand and address. Within the ESRS, the standard S3 deals with the issues of affected communities, such as noise or privacy. Early consideration of these aspects have placed RigiTech ahead in the “sustainability race”.

Figure 2: Disclosure requirements of ESRS S3 Affected Communities

What’s next?

The importance of sustainability for drone businesses is expected to increase, regardless of the business size. Even in developing contexts, where regulations are not as strict as in the EU, sustainability matters are essential for business strategy. The effective identification of material environmental, social and governance matters can leverage service quality, community support, prevent sustainability risk, and ultimately, result in great economic, environmental, social and governance impact.

about the authorS

Pablo Busto Caviedes

Pablo specialises in monitoring and evaluation (M&E), policy research, qualitative and quantitative data analysis. His experience includes a diverse range of social and economic development topics such as rural development, agriculture, or social inclusion. He currently primarily works as an Impact Analyst for evaluation studies at another non-profit organisation.

Denise Soesilo

Denise is an expert in drone technology and social innovation particularly in humanitarian and development settings.

Bo Jia

Bo has supported several digital agriculture projects, covering topics such as M&E, digital finance, e-commerce, drones, pushing for programmatic and strategic approaches to analyse digital products and investments in the organisation.

Edited by Maria Zaharatos

If you’d like to keep up the discussion, learn more or see how we can help, please get in touch.