WHO estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will cause about 250,000 additional deaths per year due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea, and heat stress alone. Climate change affects human health through multiple pathways, including heat stress and air pollution, as well as food insecurity and mental health. Organizations and policymakers are challenged to understand and prioritize potential policy levers and measures to adapt to or mitigate impacts on human well-being. To credibly quantify the health impacts of climate change, researchers must embrace a blend of data sources including Earth Observation and multimodal approaches to causal inference.

How will the European Union sustainability reporting requirements affect the drone industry?

The New European Sustainability Reporting Space

Corporate sustainability reporting is rapidly evolving worldwide. Previously relying on a wide range of industry-led reporting systems, standardization is now becoming a reality, especially in the European Union (EU).

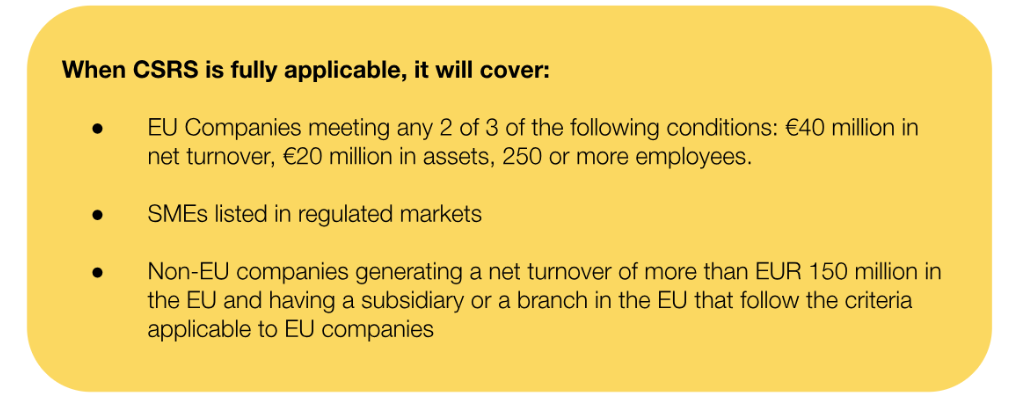

An important milestone was achieved earlier this year, when the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) entered into force. Large public interest companies will be required to report on their 2024 ESG metrics and provide data in a machine readable format (XHTML) to the European Single Access Point (ESAP). Progressively until 2028, more companies will be required to report, including non-EU companies operating in the European market.

Within this space, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) provide an official comprehensive framework for sustainability reporting. However, when an impact, risk or opportunity is not sufficiently covered within the standard, businesses may need to use additional sector-specific or even develop entity-specific disclosures.

Disclosures comprise quantitative and qualitative data on environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters, covering short, medium, and long-term horizons and the company’s entire value chain. Assurance of ESG data will be provided by statutory auditors (legally required) or an accredited third party. Currently the standard is limited assurance, but in the future, reasonable assurance may be required, a more rigorous level now used for financial data.

What sustainability aspects should the drone industry consider?

Most drone industry organizations are not directly affected by CSRD because they do not reach the size thresholds for mandatory reporting. However, the drone industry, like any other, will have to incorporate sustainability strategies to operate in increasingly sustainability-sensitive markets, in the EU and elsewhere.

In a relatively emergent industry like drones, sustainability frameworks and the associated metrics, adequate policies, actions and targets are not as consolidated as for more mature industries like textiles, agriculture, oil or gas. There is still a lack of sectoral standards on drones’ sustainability, but progress is being made in related fields. For example, sectoral standards for motor vehicles are under development within the European CSRD framework.

Prior to reporting, drone businesses have to look at their direct sustainability impacts and risks. Probably the first environmental (E) issue that comes to mind is the manufacturing of drones and their waste disposal. This is indeed important and not much different from other electronic industries. Technical expertise and engineering solutions together may result in procedures that integrate these matters to make the product management process as clean as possible.

Drones business will also have to consider the social (S) impact of their activities towards their own workforce or workers in the value chain. Similarly, from a governance point of view (G), drone business should consider business conduct.

Drones business will also have to consider the social (S) impact of their activities towards their own workforce or workers in the value chain. Similarly, from a governance point of view (G), drone business should consider business conduct.

Nevertheless, the most relevant sustainability matters for drone businesses will be specific to the type of activities that a company is engaged in. These relevant environmental, social and governance matters will be deemed material using sustainability jargon. The challenge is that assessing materiality is not always as straightforward as it seems.

How does a drone company know what issues are most relevant for its reporting?

A materiality assessment is a critical process that helps companies identify and prioritize the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues most relevant to their business and related stakeholders. Incorporating human-centered design principles, this assessment ensures the company's sustainability reports focus on significant impacts and risks, aligning with regulatory requirements and stakeholder expectations. By engaging with internal and external stakeholders, companies can determine which ESG topics are material, enhancing transparency, accountability, and strategic decision-making for risk management and impact enhancement. Ultimately, a robust materiality assessment fosters trust and drives long-term value creation.

Material topics for drone business may comprise topics such as privacy, noise, safety, fear, misconceptions, and other issues affecting communities. For example, for companies providing drone services for agriculture, privacy and noise won’t be relevant matters, but noise and privacy will be of utmost materiality for a drone company transporting medical supplies in urban areas.

Additionally, drone businesses should consider indirect sustainability implications. The most common is that drone businesses may be required to provide data to larger client companies that buy drones or use drone services to include the drone company ESG data in their sustainability reports. For example, the GHG emissions of a drone service provider may need to be accounted for as part of the upstream emissions of a large company (referred to as scope 3 emissions).

Drones may also be used as tools for the sustainability strategy of a larger company. For example, electric drones may be used as a mitigation tool to reduce overall GHG emissions for large companies. Similarly, drones can improve safety conditions for workers inspecting infrastructure in hazardous environments, such as heights or hard to reach locations.

How can drone businesses put sustainability matters into practice?

Figure 1. Noise map of the flight path across lake Geneva and at landing generated with SAFTu

Recently we worked with Rigi Tech to identify and mitigate material community impact of their drone delivery across Geneva lake. In this project, one the most relevant material aspects was drone noise, which we helped Rigi understand and address. Within the ESRS, the standard S3 deals with the issues of affected communities, such as noise or privacy. Early consideration of these aspects have placed RigiTech ahead in the “sustainability race”.

Figure 2: Disclosure requirements of ESRS S3 Affected Communities

What’s next?

The importance of sustainability for drone businesses is expected to increase, regardless of the business size. Even in developing contexts, where regulations are not as strict as in the EU, sustainability matters are essential for business strategy. The effective identification of material environmental, social and governance matters can leverage service quality, community support, prevent sustainability risk, and ultimately, result in great economic, environmental, social and governance impact.

about the authorS

Pablo Busto Caviedes

Pablo specialises in monitoring and evaluation (M&E), policy research, qualitative and quantitative data analysis. His experience includes a diverse range of social and economic development topics such as rural development, agriculture, or social inclusion. He currently primarily works as an Impact Analyst for evaluation studies at another non-profit organisation.

Denise Soesilo

Denise is an expert in drone technology and social innovation particularly in humanitarian and development settings.

Bo Jia

Bo has supported several digital agriculture projects, covering topics such as M&E, digital finance, e-commerce, drones, pushing for programmatic and strategic approaches to analyse digital products and investments in the organisation.

Edited by Maria Zaharatos

If you’d like to keep up the discussion, learn more or see how we can help, please get in touch.

Is it time to admit that Innovation Pilots don’t work?

In the 16th century, bloodletting was a trusted treatment for many ailments. It was widely used by experienced professionals, despite the fact that it didn’t work and actually killed many patients, including George Washington.

Why wasn’t it obvious that this treatment was a failure, and why was it a go-to treatment for hundreds of years leading up to the 19th Century? Before we shake our heads in condescending hindsight, we should ask ourselves a more current question: Why do innovators working in the complex varied contexts of humanitarian aid and development continue to invest in Silicon Valley-inspired pilots?

The scenarios are far more alike than we’d like. One humanitarian innovation lab leader described the portfolio of pilots they had supported as a ‘cabinet of broken dreams’, while another international aid innovation program executive quipped that they ‘would have to get a bigger budget to build more shelves’ to hold all their failed pilots.

It’s not simply that innovation pilots have a horrendous record of success at scale. My work as an innovation advisor, coaching ‘promising’ pilot programs, has often revealed that pilots lead project teams in the wrong direction and that, frequently, the only path forward is to tear most of the work down and start over with a different mindset.

Can we save the practice of innovation pilots in aid? Or, is it time to admit that pilots, which a decade ago seemed like such a good idea, just aren’t working?

ANSWERING THE WRONG HARD QUESTIONS

The basic idea behind pilots as we know them seems sound. We should as quickly and cheaply as possible answer the hard question(s) that determine the success of our proposed innovation. In Silicon Valley, where the current pilot practice emerged around 2010, that big question was usually “Is there a market for this idea?”

In the aid sector, the pressing question is more often framed as “does this idea deliver value?” Pilots build out a lightweight version of the idea and then develop measurable evidence of its impact.

However, this is seldom the hardest or even most consequential question in a complex and messy aid context.

What the sector has found over a decade of investment is that even great pilots fail to work in practice, get adopted, or be sustainably operated. Complex challenges and unanticipated barriers mean that, despite many pilots’ early promise, there is often exactly zero impact.

And yet, most pilots are still intentionally designed to be simple and lightweight, avoiding hard questions like:

What is the sustainable business model?

How will the innovation integrate with other technologies and operations?

Who will actually be motivated and able to adopt the solution?

Who will remove key political, technical, or collaborative barriers?

How will key gaps in capabilities and resources be filled?

In a study that Hannah Reichardt and I did for DG ECHO, we identified over 50 complex challenges that technology innovators in the aid sector face, and that need to be addressed over the full lifecycle from ideation to eventual scaled operation.

Pilots are not in the business of asking and answering so many hard questions. So they often finish their time-boxed project without a sense of what their most difficult challenges are, whether they can be addressed, and how they can find a way forward.

To indulge in metaphors again, this is like setting out on an arduous journey through an unmapped mountainous jungle and proudly announcing that you’ve prepared by picking out a good pair of socks… Potentially useful, but woefully insufficient for the (scaling) task ahead.

POINTING CONFIDENTLY IN THE WRONG DIRECTION

Aid sector innovation programs have begun to recognize the size of this gap and stepped in to fill it. Labs increasingly offer extended funding to support innovators after their initial pilot project. They are also providing skilled coaches to help innovators fill in the missing parts of their solutions. This is a substantial investment, and if it addressed the one shortfall of pilots, it might well be seen as the natural development of the sector’s innovation practice.

Unfortunately, pilots have an even deeper defect. They encourage an immature rush to judgement, thinking that leads to naive views of complex challenges and small solutions that fail to make the best use of precious innovation investments.

As innovators working in a field where people’s lives and wellbeing hang in the balance, it is not enough to simply develop ‘a solution’ to ‘some problem’. As a matter of strategic policy, we should be looking to address the most important challenge with the best solution possible.

The typical pilot ideation and funding process does little to drive toward this higher standard.

Pilots are typically rooted in someone’s creative idea. The idea might emerge from an innovator’s personal experience, a hackathon event, or a call for proposals. There can be a lot of energy around this part of the work (so innovators like to do it), and the resulting neatly bound ideas are easy to fund (so donors like to support them).

This natural rush to ideation and the enabling pilot funding often sidestep a big-picture view of the challenge. As a result, innovators fail to see where the most impactful opportunities are or recognize the need for more sophisticated solutions. This harder messier version of a challenge might well not have a quick and neatly boxed-up pilot project as its solution. Hans Rosling in his fabulous book Factfullness relates the story:

““[During the Eboloa outbreak] we had hundreds of health-care workers from across the world flying in to take action, and software developers constantly coming up with new, pointless Ebola apps (apps were their hammers and they were desperate for Ebola to be their nail).””

Unfortunately, pilots, much like bloodletting, are not simply innocent practices. They actively encourage innovators to indulge in quick ideation and funders to support small ideas without a clear vision of where the biggest opportunities actually lie. We waste the precious opportunity to do powerful important things when our efforts and our funding are diverted into small poorly targeted work.

JUST STOP AND MOVE ON

For nearly a decade, aid sector innovators and the programs that support them have been asking the question “How do we make pilots deliver scale at impact?” And, there have been increasingly sophisticated approaches to the work.

But maybe it is time to just stop.

Innovation in the aid sector is too important to continue pursuing a structurally unsound practice that doesn’t fit the challenges the sector faces. It may seem radical, particularly given the amount of effort and culture change that has been invested in making pilots part of aid sector practice. Nonetheless, if pilots don’t work for complex, varied, and messy aid sector challenges, it will be better to look for better practices.

Increasingly, there are changes on the ground that move in this direction. Both innovators and innovation funders are shifting their approach, setting aside key elements of the Silicon Valley-inspired pilot model for a more systems-based approach:

A climate action organization is systematically mapping out the entire complex ecosystem of organizations, technology, policy and resources in the challenge areas where they plan to invest in innovative action.

The Response Innovation Lab (RIL) routinely steps back and develops a big-picture view of humanitarian challenges in the countries where they work.

Innovators working on aid sector goals like localization of purchasing or circular economy in humanitarian aid are starting with solutions that have multiple interconnected parts instead of an overly simplified piece of the solution.

In each case, complexity is recognized and embraced from the beginning. These innovators, and their funding sponsors, see this complexity as an opportunity to claim a bigger more impactful challenge and then develop a sufficiently ambitious solution.

However, these more thoughtful programs don’t throw out all the good lessons about nimble learning that were part of the pilot practice. They move with urgency and learn from action. They iteratively evolve their sophisticated solutions, actively engage stakeholders, and are willing to pivot and adapt along their journey.

The difference is that they have identified the hard parts up front, and therefore look to answer the hardest and most important questions early on. That might be, “What’s my long term funding strategy?” Or “How will we get this key organization to participate?”

Taking this bigger picture approach to the aid sector’s hard problems and leaning into sufficiently complex solutions will almost certainly result in fewer projects than were possible in the heyday of pilots. But, it also has the potential to set us on a path to far more initiatives that actually deliver impact at scale on problems that really matter.

about the Author

Dan McClure

Dan McClure has spent over three decades working on the challenge of disruptive and complex systems innovation. He has advised global commercial firms, public sector agencies, and international non-profits in support of their ambitious efforts to imagine and execute agile systems level innovation. He is an author of the book "Do Bigger Things - a practical guide to powerful innovation in a changing world.”

Equitable Pathways to Success: Transforming Digital Education and Opportunity Matching

Digital tools are increasingly vital in addressing complex challenges such as youth skill and opportunity gaps and high unemployment in many parts of the Global South. Catalyzed by adaptations due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the online interface is now increasingly relevant in education from remote learning and online certifications to job matching.

These technologies democratize access to educational content, benefiting millions gaining internet access each year in emerging economies. As always, along with the promise they hold, there are a plethora of pitfalls.

CHALLENGES IN EDUCATION AND OPPORTUNITY MATCHING

Numerous platforms have emerged that aim to address youth training needs, such as digital skills in IT, web development etc. They also provide key staffing for businesses and organisations struggling to identify talent in tight labour markets and to fulfill their CSR goals.

Yoma, an ecosystem of partners including but not limited to UNICEF, Atingi, UMUZI, and RLabs is one such example, connecting youth to opportunities for learning and earning in over 8 countries. The government of South Africa has also developed the SAYouth platform to address these issues and tackle the country’s unemployment crisis. Likewise, in Germany, the ReDI School of Digital Integration upskills youth with a migrant or marginalized background to accelerate integration into the digital economy.

Despite the benefits from these types of programs being globally or nationally accessible, they often struggle to localize to the needs of culturally and socially-diverse users, especially those belonging to marginalized populations.

Delivering effective and equitable matching with opportunities thus becomes a challenge, as candidates from different countries, with different backgrounds and levels of education are exposed to and compete for the same training or earning opportunities.

Additionally, not all opportunities can be available to every young person, and in many cases spots for learning or earning opportunities are limited. Selection processes, often ‘funnel’-based, lead to many youth being excluded due to mismatches with predefined criteria or aptitude tests specific to the job or training opportunity.

These selection structures pose two major challenges.

CHALLENGE #1 Due to the nature of the funnel, a large population of youth fail to receive benefits as they are filtered out. In doing so, this also reduces the candidate pool for employers. Each failure to match a candidate to training or opportunities can be seen as a lost chance to deliver impact - we run the risk of excluding the most vulnerable, the population we seek to reach.

CHALLENGE #2: Bias in the filtering process further compounds inequities, as candidates may be funneled out by the selection criteria for factors such as educational attainment, language skills, time availability and internet access. Even though this is a data driven approach to identifying the best candidate, there are underlying risks of bias in the selection process. For example:

Educational attainment achieved as a proxy for gender: in many contexts, women are less likely to reach the highest levels of schooling.

Time availability as a proxy for gender: women with children will have to spend their time on childcare. As such, women might be less likely to be able to commit to the requisite amount of time for training programs.

Language as a proxy for ability: if the selection process for training programs includes language assessments, this can filter out candidates who have a strong ability — for example in STEM subjects — but who do not get through the application process because they misinterpret test questions.

Internet access as a proxy for economic status: if a candidate only has limited access to the internet, they may be rejected from a training program, but this might well be as a result of their socio-economic background.

Whilst it is logical that training and career development programs look to identify candidates with a suitable CV for their programmes, it is also important to account for such biases during the selection process.

Indeed, these challenges are not new, as the development sector has long struggled to find a balance within ICT between innovation and equity/inclusivity. So, how can we best leverage the potential of these innovations in education, without leaving the most vulnerable behind?

Revised Applicant Selection Process. Sankey Diagram

RECOMMENDATIONS

Although more complex, the recommended approach offers a suitable opportunity pathway tailored to the needs of each candidate. At Outsight, we build on the range of expertise offered by our network of associates in order to deliver quality results adapted to the specific tasks at hand.

We believe it is developing these kinds of complex approaches that maximizes sustainability, effectiveness and impact.

Transitioning from Funnels to Matching

A strategic shift: Moving away from funnel-based selection to matching candidates with suitable opportunities can reduce dropout rates and bias in the narrow selection process.

Opportunity for all candidates: Rather than narrow criteria focused on a specific role or type of training, programs could evaluate candidates based on diverse skills and match them to relevant opportunities (ie. mentorship and entrepreneurship training or further skills development activities)

The result? A larger percentage of candidates access an opportunity and are matched to those where they can succeed. This approach is structurally designed to broaden access to opportunities for a wider range of candidates with diverse backgrounds and talents.

2. Proactively address bias with a data driven approach

Identify and Mitigate the Impact of Bias: A matching approach opens up more paths, considering a richer view of candidates and their context. As such, it reduces the impact of bias in underlying data and data-driven algorithms.

Using Data to Understand Bias: Instead of “weeding out” candidates, aptitude tests could help counteract bias by collecting candidate age, gender, education, location, internet access, education, refugee status etc. The resulting dataset provides an opportunity to better understand the variables and structural biases that determine whether an applicant possesses the relevant skills to pass the test.

Exploring algorithms: Using a systems approach and data analysis, programs can develop more complex and useful algorithms that prioritize equity of opportunity for youth.

Ultimately, for programs to be transformative and truly unlock new opportunities for young people, the methodologies they use must place equity at the center.

about the authors

Denise Soesilo

Denise is an expert in social innovation particularly in humanitarian and development settings.

Maria Zaharatos

Maria is a consultant specializing in research, program design, partnership development, and organizational systems, who champions co-creation and engagement with stakeholders. Her areas of focus are green education, youth empowerment, and workforce development. She has supported various education-focused programs and organizations, including UNICEF, where she helped develop key partnerships and implementation strategy for Yoma’s scaling across the East and South African region.

If you’d like to discuss working with the Outsight team, please get in touch or follow us on LinkedIn for regular updates.

Navigating the challenges of humanitarian-academic collaborations

Image credit: International Committee of the Red Cross/Jacob Zocherman.

In the quest for innovation and progress, partnerships between humanitarian and development organisations (HDOs) and academia have become increasingly common. However, a recent article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) sheds light on the practical challenges faced by such collaborations. Authored by Louis Potter — Managing Partner at Outsight — and a group of seasoned innovation practitioners, the article critically analyses the dynamics of partnerships between HDOs and academia, emphasising the need for a more strategic and efficient approach.

Link to the Article: Read the Full Article

Understanding the Landscape

The article delves into the motivations behind collaborations between HDOs and academic institutions. Highlighting the involvement of prominent organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Doctors Without Borders (MSF), the authors acknowledge the noble intentions of these partnerships—to leverage academic research and scientific expertise to address real-world problems in challenging environments.

Identifying Pain Points

Through a critical analysis informed by workshops and interviews, the authors identify three main categories of pain points along the technology development timeline: resources, deployment strategies, and roles and responsibilities. Each category poses unique challenges that, if not addressed proactively, can hinder the success of collaborative efforts.

Funding and Human Resources:

The article emphasizes the importance of securing adequate funding throughout the project duration.

Challenges arise from differing expectations between HDOs and academia regarding funding sources and project scopes.

A lack of commitment of human resources from both sides hampers the initial stages of project development.

Deployment and Sustainability:

The success of a technology is measured by its deployment on a wide scale, yet this remains a rare outcome.

The article highlights the lack of profit motivation, leading to neglect in maintenance, improvement, and training for deployed technologies.

Questions of self-sustainability and market outreach are critical considerations often overlooked in early project stages.

Roles, Responsibilities, and Expectations:

Clear definition of roles and responsibilities is identified as crucial for successful partnerships.

The authors argue that the classic academic approach to technology development may not perfectly align with the requirements of HDOs.

Expectations play a significant role in determining the success of partnerships, emphasizing the need for transparent communication.

Moving Forward

The authors advocate for a more strategic and informed approach to collaborations between humanitarian and academic sectors. They stress the importance of comprehensive planning, clear communication, and a critical partner selection process. The article concludes by calling for a literacy in technology innovation and development processes within HDOs to ensure a more nuanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities presented by collaborative initiatives.

Conclusion

As we navigate the complex terrain of humanitarian-academic collaborations, the insights provided by this PNAS article serve as a valuable guide. Acknowledging the inherent challenges and proposing solutions, the authors encourage stakeholders to approach partnerships with a strategic mindset, fostering a more efficient and impactful collaboration that addresses real-world challenges in a holistic manner.

Launching drone (UAS) deliveries for health operations: Five learnings from real-world projects

In recent years, Outsight International’s Drone Team has worked with development organisations and national civil aviation agencies (CAAs) across Africa and Asia to advance health solutions using drone technology.

Health supply chains in many developing countries face important challenges, like insufficient cold storage and road infrastructure and in rural areas, fragmented management, safety concerns or limited availability of trained staff. Furthermore, each medical product has its own characteristics, making it difficult to find a solution that works for all items. For example, vaccines require a reliable cold-chain, and have a fairly predictable demand, while blood or anti-venoms have a much harder to predict demand as sudden peaks of demand may occur in any particular location.

Drones – also referred to as uncrewed aerial systems or UAS – can help address some of these supply challenges by quickly reaching remote locations from well-equipped warehouse facilities. There are many experiences of these uses across the world; drones have been used to deliver emergency medical supplies or tests in Malawi, vaccines have been delivered in Vanuatu, and extensive drone delivery networks for blood and other health products on a regular basis have been operating in Rwanda and Ghana for a few years. However, drones are not a magical solution for all health supply issues in any location. In this post, we share five key learnings emerging from our practice:

1. Understand the challenges of the health supply chain

Prior to developing a drone medical delivery system, it is important to understand what works well and what can improve in the existing supply chain of health items. Drones may be suitable to cover some gaps, but not all. A comprehensive supply chain assessment with a systems-thinking lens will avoid common pitfalls derived from a lack of understanding of the ecosystem in which medical transportation happens.

2. Assess the feasibility of drone deliveries

Even if some identified gaps of the health supply could improve by using drones, they may still not be a feasible solution. Drone suitability also depends on many non-health related factors, such as the drone parts supply chain, technical feasibility, maintenance, workforce available, or community engagement. One of the hardest issues to assess in advance are costs and cost-effectiveness of drone operations with respect to alternative means of transportation.

3. Regulation is a key enabler of drone operations

The regulatory environment is an essential factor to analyze when launching any drone program. However, as health deliveries involve relevant risks and operational complexities, regulatory requirements are more strict than other drone use cases.

In recent years many countries have approved regulations that include provisions on how drones can be operated, what authorizations are needed, what uses are forbidden or what are the requirements to prevent harmful uses. For health operations, some relevant rules to consider typically include limitations on cargo drops, weight limits, operations beyond visual line of sight or transportation of dangerous goods.

On the other hand, some countries do not yet have drone regulations in place. In these cases, some governments have allowed certain ad-hoc drone operations, but the lack of legal certainty is an important barrier for the development of the civil drone ecosystem. As the international drone regulatory ecosystem has been maturing, countries that plan to adopt drone regulations may benefit from comparative expertise including International Civil Aviation Organization model regulations, best practices from other countries in their region, or technical assistance from drone policy experts.

4. Procedures and supporting materials are essential to put legislation into practice

Drone regulations are a basic enabler for health operations, but not enough. National civil aviation agencies need complementary procedures that link abstract regulations with day-to-day practices in order to run drone operations safely, securely, and efficiently. Relevant procedures include drone operator registration, drone registration, type certificate acceptance, airworthiness verification or operations manuals.

5. Capacity building facilitates implementation

Capacity building and training of personnel involved in drone projects is essential for a successful implementation of healthcare drone operations. Limited capacity is a common challenge that often introduces significant delays and higher risks in operations.

To support local capacity, ICAO and drone experts provide technical assistance to civil aviation agencies at the country level. Additionally, initiatives like UNICEF’s African Drone and Data Academy also contribute to the development of local capacity to build, use and maintain drone technology.

The drone team at Outsight International supports NGOs, businesses and governments on their journey to leverage drones. We offer omni comprehensive services from piloting a small scale UAS program to developing a national drone policy, including market research, cargo and supply chain integration, or our own methodology 360 feasibility studies.

Bonus tip: As with any innovations, is it important to incorporate monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) to programming. Emerging technologies and pilot projects often have limited data on their impact so a solid MEL system can provide evidence for decision making and support a case to scale, allowing organisations to maximise their impact, accountability and learning.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Denise Soesilo

Denise is an expert in unmanned aerial system (UAS) use in humanitarian and development settings. She has worked with donor agencies and development organizations, humanitarian and United Nations organisations, advising on the application and implementation of drone technologies. Denise served as the director of flight in the African Drone Forum - Lake Kivu Flying Competitions and implemented numerous other drone operations. Through her work, Denise has enabled the safe operations of nearly a dozen cargo drone companies. In addition, Denise has led the implementation of the European Union Humanitarian Aid innovation grant on drones in humanitarian action. Denise has authored several publications on UAS in development and humanitarian action.

Pablo Busto Caviedes

Pablo specialises in monitoring and evaluation (M&E), policy research, qualitative and quantitative data analysis. His experience includes a diverse range of social and economic development topics such as rural development, agriculture, or social inclusion. He currently primarily works as an Impact Analyst for evaluation studies at another non-profit organisation.

Prevention of adolescent mental health conditions: is technology a possible source for good?

In 2021, in a bid to explore the transformative potential of technology in adolescent mental health, the Data for Children Collaborative with UNICEF embarked on a groundbreaking project with Outsight International, in collaboration with UCIPT and ElevateU. The first phase of this initiative, divided into seven investigative areas, laid the groundwork for understanding existing systems and landscapes crucial for developing effective programs. These areas were:

Systems View of Digital Health Ecosystems (Outsight International)

This work package delved into the complex digital health ecosystem, creating system models that serve as tools to identify relationships and patterns. By adopting a holistic approach, the team aimed to avoid narrow solutions and recognize the diverse elements of a digital health solution.Overview of Available Data Types (UCIPT)

The project explored a myriad of public and private data resources, from social and health data to consumer and satellite data. This early exploration provided insights into the possibilities for moving towards an implementable project.Review of Digital MHPSS Tools Literature (ElevateU)

Recognizing the growing importance of adolescent mental health, a literature review was conducted to understand the impact of technological interventions. The review, encompassing 38 articles and 14 from grey literature, highlighted the overwhelmingly positive impact (98%) of technology on adolescent mental health.Technology Landscaping of MHPSS Digital Tools (Outsight International)

An effort to understand relevant digital health solutions was initiated to act as a reference point for ongoing evaluation and context-specific needs.Data Landscaping and Key Informant Interviews (Outsight International)

Interviews with mental health researchers, funders, and service providers revealed a broad consensus that technology's impact on adolescent mental health is nuanced and context-dependent.Workshop Sessions (Outsight International)

Two workshops focused on compounding factors influencing mental health outcomes, leading to the identification of three key research questions. These questions aimed to understand platform usage, adolescent interactions with online technologies, and the potential for existing platforms to adapt for better services.Phase 2 Conception

Integrating UNICEF's Measurement of Mental Health Among Adolescents at the Population Level (MMAP) approach with digital mental health interventions was proposed for Phase 2. This approach offers an opportunity for a multi-cohort longitudinal study in Jamaica, testing the effectiveness of digital tools and improving data collection methods.

In conclusion, the collaborative and human-centered approach of the project, grounded in a systems perspective, has paved the way for a comprehensive Phase 2. This ambitious next step aims to improve access to services, enhance data collection systems, and provide valuable insights for UNICEF's programming not only in Jamaica but also as a comparative study across other focus countries. As the project advances, collaboration between the Data for Children Collaborative and UNICEF will define the scope, identify partners, and secure funding, marking a significant stride towards better adolescent mental health worldwide.

How to deal with Intellectual Property Rights in humanitarian innovation

Outsight International recently supported the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in developing an intellectual property (IP) framework to help staff navigate the complex — and sometimes scary — world of IP. In this post we discuss the common concerns that those unfamiliar with the topic face when understanding their options and choosing an IP strategy.

Why is intellectual property an issue in humanitarian innovation?

Humanitarian innovation refers to the creation, adaptation, and application of new solutions to address challenges faced by individuals and communities affected by crises. These crises can include natural disasters, conflicts, epidemics, and other emergencies.

Over the last decade, humanitarian innovation has led to many new products and services being designed and implemented. These might be hardware, software creations or processes. Unlike the private sector where the end goal is to create profit from these products/services, the the primary goal of humanitarian innovation is to improve the effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of humanitarian efforts in providing assistance, protection, and support to those in need.

Although different in their goal, humanitarian innovators usually have to work with IP tools created for the private sector, which can lead to fear and a lack of clarity as to what’s the best approach to reach their goal.

This is for a number of reasons: firstly, IP is seen as an incomprehensible legal topic; second, the perceived risk of getting anything ‘wrong’ in the legal space is greatly feared; and thirdly, many practitioners in the humanitarian/development space see intellectual property rights as a negative thing, usually employed by the private sector to protect profits over people. We now breakdown these fears and try to allay them.

FEAR #1: IP is too complicated to grasp

To say that IP is not complicated would be unfair — there are indeed a lot of component parts to think about: types of IP protection, extent of IP rights, enforcement in multiple jurisdictions, contract wording, registration processes, etc. Among unacquainted innovators, the questions we often hear are:

‘How do we file a patent?’

‘Should the organisation own patents at all or should we aim to share the innovation as widely as possible for public good?’

‘How can we prevent others from appropriating or misusing an innovation?’

‘Is it worth it to spend resources enforcing patent protection in a fragile context?’

‘Are open source licences always the best alternative for our software?’

‘What is a licence?

‘Would all of this be the same if the innovation has been developed in partnerships with the private sector?’

‘What if the partner is a university?’

Despite all this confusion, IP can be simplified by thinking about options in straightforward language. At a base level, intellectual property can refer to anything created by the mind. This asset could be incorporated in a tangible creation (such as a newly invented device or a piece of art), but not necessarily (it could also be a process, a design, a trademark, or software). Intellectual Property rights comprise a range of rights over a creation, including economic and moral (being recognised as author).

In simple terms IP rights determine who is entitled to use that creation and under what circumstances. To protect these rights, a wide range of mechanisms are available, which can be roughly grouped into three categories: legal, contractual and informal.

First, legal mechanisms (often referred to as formal IP protection) offer the most sophisticated safeguard, but require technical knowledge and are harder to enforce, especially in fragile jurisdictions. Among these legal mechanisms, some require a complicated registration process (e.g., patents or utility models), while others are automatic (e.g., copyright) or easy to use (e.g., copyleft or FOSS licences).

Second, contractual mechanisms are agreed rules embedded in partnerships, employment or consulting contracts. Some examples include confidentiality or recruitment freeze clauses.

Last, informal mechanisms comprise all other protection mechanisms not emerging from laws or contracts, such as secrecy, protective publication, documentation, division of duties, and many others.

Fear #2: Getting IP ‘wrong’ is high risk

One of the main reasons humanitarians are so fearful of IP is because they believe there is a right and wrong way to deal with it. This is not the case. IP clauses written in contracts are — at their base level — just a fancy-worded version of a decision of ‘who has the right to use a creation and how?’.

In some instances, this decision will be influenced by existing IP rights — for example, when adapting something existing you will be bound by the IP rights of that existing thing, or an employee contract might dictate who owns creations invented during work activities. In instances of ‘true’ invention, there is a decision to be made based on a spectrum from closed to open, which also involves an assessment of risks and trade-off.

To determine what IP approach makes the most sense, innovators should consider not only what goals they are aiming for and what resources they have, but also what risks are involved. A systematic risk assessment must be conducted considering risk for the users of the innovation, risks for the organisation and its members, risk for third parties and risks for the innovation and its sustainability.

For example, disclosed IP may be used by third parties for unintended purposes, negatively affecting vulnerable groups. Organisations should consider the diverse profile of people in terms of gender, age, location, legal status or any other personal circumstances that might put them at harm due to IP disclosure to other parties.

FEAR #3: IP protection serves profit maximisation, not humanitarian goals

Historically, intellectual property rights were developed to protect economic and moral rights of creators, with an understanding that this would also facilitate innovation and fair knowledge sharing. Patents, the most IP protection tools, were designed to control who can access innovations, which is very well suited for the patent owner to exploit the innovation and make profits out of it. However, ethical concerns may arise if access to an essential innovation is limited by economic or legal barriers. In recent years, COVID-19 vaccines reignited this debate, with many government and international organisations advocating for a waiver on patent protection to facilitate vaccine accessibility.

Within this context, it is understandable that IP raises suspicions among many humanitarian staff as a tool tailored for profit maximisation, not humanitarian goals. However, since IP rights can be highly customised, humanitarian actors can use them for their own goals as well.

Overall, humanitarian organisations aim to maximise positive impact for people affected by armed conflict and violence. The most logical assumption is that people would usually be better off benefiting from an innovation, and therefore, in principle humanitarian organisations are likely to lean towards more open access IP approaches than the private sector. Open IP approaches allow collaboration, reuse and a more efficient resource allocation in the sector as a whole.

However, even open approaches involve some kind of IP strategy and management to meet the goals of the humanitarian sector. For example, software creators may want to share their code for reuse in the sector, but they still need to make a thoughtful decision among multiple free or open licences, each with its own characteristics, as well as understand the risks, resources and trade-off associated with it.

There are IP options available to innovators which require little ongoing management. Protective/defensive publication is one such tool. This involves publicly disclosing detailed information about an invention to prevent others from patenting the same idea. While the disclosure may not result in obtaining a patent, it acts as a defensive measure to ensure that others cannot claim exclusive rights to the invention.

Developing an IP framework

To address these concerns and develop a common IP understanding within an organisation, it is recommended that organisations working in the humanitarian innovation space develop a comprehensive IP framework, tailored to the organisational context.

In close contact with internal stakeholders and informed by sectoral best practices, the IP framework serves as a clear guidance for decision making, informed by humanitarian principles, risks, and resources available.

Outsight International can help organisations to this end: having already worked on hundreds of innovation projects aiming to serve the public good and helping organisations create these frameworks. If you’d like to learn more or you think we can help, please get in touch.

About the authors

Louis Potter

Louis has a wide range of experience covering development, health, innovation, technology and research. He has worked on over 100 humanitarian initiatives and helps humanitarian organisations, universities and companies to improve innovation processes and outcomes. Recently, he has been helping actors navigate paths to scale in the humanitarian sector and strategise business models.

Pablo Busto Caviedes

Pablo is a researcher with a legal background, who specialises in monitoring and evaluation (M&E), policy research, qualitative and quantitative data analysis. His experience includes a diverse range of social and economic development topics such as rural development, agriculture, or social inclusion.

Addressing drone noise pollution: a public engagement perspective from the front lines

By Denise Soesilo and Bo Jia

We began our journey in 2015 helping organisations and health actors plan out and implement medical drone operations in rural settings. However, as technology has advanced, we see more exciting projects that bring drone deliveries into urban areas. One example is the planned Rigi Tech operations across Lake Geneva in Switzerland, proposing daily deliveries of medical samples between doctors offices in Rive Gauche and Coppet across the lake. The hope is to cut health care system costs, reduce emissions and remove cars off the streets, which everyone agrees is great. But this also brings drones closer to where people live and work every day and raises questions with regard to new types of noise pollution.

Urban Air Mobility (UAM) is defined by EASA as an air transportation system in and around urban environments providing connectivity within the cities and among regions. In recent years, Europe has been perceived as a market leader in the development of UAM. According to EASA, the European UAM market size is predicted to be 4.2 billion EUR by 2030 (see the report we wrote together with the European Institute of Innovation and Technology for more details).

According to an EASA study on social acceptance of drones, noise is the second main concern after safety. The study concluded that people often find drone noise more annoying than other city sounds. To develop sustainable UAM in Europe, it’s thus critical to address the noise-related concerns expressed by EU citizens. We found that technical and policy guidance is slowly emerging but many unknowns still need to be solved.

From a technical perspective, there are ways to make a drone quieter, such as using noise-reducing propellers and noise-reduction shrouds. The industry is working full steam on these approaches and whilst critical, there are also important social elements that need to be addressed. In the following we discuss what we have learned about how to effectively address people’s concerns through public engagement.

The core of this approach is twofold. When engaging with communities we have learned that transparency and early engagement are key. In addition, technical elements and available information needs to be compiled and shared in a way that helps communities engage in a meaningful way. This also signals that industry players are applying best practices to address any potential issues.

The first step is to ground discussions on facts and data as much as possible and to provide transparency. This means actual drone noise data needs to be collected and modeled or measured in situ. This data will be crucial to inform the affected neighbourhood as well as report to local authorities. This data will be complemented with ancillary information such as prevailing regulations and noise pollution benchmarks. The second step is to enagage the community and understand their perception and fears. Often the history of the community plays a strong role in beliefs and perceptions about noise and industrial projects. If a community has previously had poor experience with environmental nuisance, then this will likely also come to the fore during these discussions.

Measurement of Drone Noise

The measurement aspects are an evolving topic, and there are still gaps in academia and practice. Although different projects and research teams have tried to measure the noise, there is currently little industry standard or binding regulation in this domain.

In a real-life measurement, the steps of different approaches include noise metrics selection, test environment conditions, drone spatial positioning, microphone characteristics, and mathematical modelling. It is a technical activity that requires specialised equipment and scientific methodology. Currently, the most relevant guideline is the EASA draft guideline published in 2022 on noise level measurements for drones below 600kg. This guideline is intended to be used on a voluntary basis and does not constitute applicable requirements for the certification of drones, but it also points to the direction for potential future regulation in Europe. It provides noise measurement standards in the specific category that includes activities such as package deliveries, powerline inspections, wildlife control, mapping services, aerial surveillance or roof inspections. The guideline detailed the entire procedure of noise measurement, including test environments, spatial positioning, speed measurement, test equipment, microphone setup, and gives detailed technical requirements for each step.

Another way to obtain noise models is through noise simulation, which requires less hardware and testing. A team from Hong Kong has measured the noise impact of delivery drones in an urban community based on a flight simulation and noise assessment platform, which contains the flight dynamics, noise source prediction and long-distance propagation modules. The EU-funded project AURORA is in the process of validating a noise pollution model. The APIS project from Stockholm also aims to establish a user-friendly platform which allows for the simulation of noise from drones.

As mentioned above, many studies have pointed out that drone noise is perceived as substantially more annoying than road traffic or aircraft noise due to special acoustic characteristics. The noise of drones does not resemble the noise of contemporary aircraft which leads to an important uncertainty in the prediction of the perception of drone noise. Different metrics such as Tonality and Loudness-Sharpness interaction might need to be measured to be able to account for the perceptual features of drone noise.

Recommendations

After obtaining noise data and understanding people’s perceptions, what can we do to address concerns? The key is when and how to engage affected communities. First of all, it’s always better to start outreach as early as possible. It can be in the form of a community meeting or roadshow that invites affected people. For the drone project team, it’s suggested to designate a person or even a dedicated unit, depending on the size of the project, to be in charge of community affairs and sensitization. This team should be introduced in brochures or on the website of the project with a detailed description of what they do. A fixed and familiar face can help win trust from the affected people.

As for the content of the communication, the accurate measurement of the drone noise should be shown to the audience. This can be a noise mapping in the neighbourhood or a printed noise report that can be handed out to the participants to form a basis of discussion along with the efforts the project is already taking to address concerns.

Besides the noise data, it’s always helpful to communicate the purpose of the drone operation. incliding any added value to the neighbourhood as well as to society that will be derived from the operation. People will more likely accept an inconvenience if it is for a positive societal cause such as the delivery of medical supplies or reducing traffic and pollution.

About the authors

Bo Jia

Bo has supported several digital agriculture projects, covering topics such as M&E, digital finance, e-commerce, drones, etc. His research helped push for more programmatic and strategic approaches to analyse digital products and investments in the organisation. He is also experienced in ecosystem mapping to identify potential investment opportunities and improve resource mobilisation.

Denise Soesilo

Denise is an expert in unmanned aerial system (UAS) use in humanitarian and development settings. She has worked with donor agencies and development organizations, humanitarian and United Nations organisations, advising on the application and implementation of drone technologies. Denise served as the director of flight in the African Drone Forum - Lake Kivu Flying Competitions and implemented numerous other drone operations. Through her work, Denise has enabled the safe operations of nearly a dozen cargo drone companies. In addition, Denise has led the implementation of the European Union Humanitarian Aid innovation grant on drones in humanitarian action. Denise has authored several publications on UAS in development and humanitarian action.

ChatGPT: the risks and opportunities for organisations in the humanitarian and development sector

ChatGPT, a large language model (LLM) developed by OpenAI, has emerged as a viable tool for improving the speed and cost of information-related work. It can help automate services, products, and processes by performing human-level information querying and synthesis instantaneously. This technology is rapidly being adopted by organisations in various sectors, including humanitarian and development organisations. However, the adoption of ChatGPT is not without risks. It is important to think about the opportunities and risks of using ChatGPT in the operations of large organisations in the humanitarian and development sector.

Some opportunities

Crisis management and communication: ChatGPT can be used to monitor and respond to global emergencies in real-time, providing a centralised communication channel for updates, guidelines, and strategies, while also addressing queries from both internal and external stakeholders.

But how?

AI assistants like Jarvis inside Whatsapp and Telegram make it possible to consult quickly on the go. It’s also possible to generate content, such as videos, faster than ever, just with text inputs.Training and capacity building: ChatGPT can serve as an interactive learning platform, providing tailored training materials, simulations, and assessments to help build capacity within the organisation and improve the knowledge and skills of professionals.

But how?

Education platforms like Duolingo and Khan Academy now have AI-powered tutors for learners, and assistants for teachers.Internal knowledge management: ChatGPT can be used to query an organisation's knowledge resources, allowing staff to quickly access information and expertise, and facilitating knowledge sharing across departments and regions.

But how?

Organisations train GPT-4 on their knowledge base, to have their own AI-powered workplace search (with AskNotion, Glean, or UseFini).Your knowledge base can become an asset, like Bloomberg are doing by training their own GPT on their financial data.

Documentation is being automatically created (e.g. for a codebase), and data entry and data cleaning can be increasingly automated with workflow tools like Bardeen.

Emergency surveillance: ChatGPT can monitor global crises as an early warning system, combining information from various sources (social media, news, and health reports) to provide a comprehensive and real-time picture of global threats, enabling swift response and containment.

But how?

It’s becoming easier and more effective than ever to scan large data streams, using models like HuggingGPT to create your own pipeline for data analytics.Public health campaigns: ChatGPT can assist in designing and implementing highly personalised effective public health campaigns by analysing target audience demographics, behaviour, and preferences, and creating customised content to maximise engagement and impact.

But how?

The founder of the world’s leading marketing platform, Hubspot, has pivoted to focusing on Chatspot, where AI helps create personalised content and marketing campaigns at scale.Policy research: ChatGPT can aid in policy research by synthesising relevant papers, data, and best practices, allowing organisations to make informed decisions and create evidence-based health policies and guidelines.

But how?

ChatGPT is excelling at summarising academic articles, blogs and podcasts.

Further still, it can elevate the capabilities of staff - no barrier to knowing data visualization languages or SQL queries by just using text commands.Grant management: ChatGPT can streamline the grant application, review, and reporting processes, ensuring that funding is allocated efficiently and transparently, and reducing the administrative burden on staff. It could also be used to raise the quality and level the playing field for applicants. Inevitably, it will be used by applicants and funded projects for reporting.

But how?

AI-powered writing tools are speeding up the process, increasing formal writing quality and helping generate ideas (Lex, WriteSonic).Stakeholder engagement: ChatGPT can facilitate engagement with key stakeholders, such as governments, NGOs, and the private sector, by providing timely and accurate information, and enabling efficient collaboration and coordination.

But how?

Effort is saved on internal communications by automatic meeting summaries, which could extend further into any type of updates.AI assistants are emerging as a way to make advice more engaging and accessible for external service users, such as this AI-powered agriculture advice for farmers.

Multilingual communication: ChatGPT can be used to automatically translate communications, guidelines, and documents into multiple languages at zero cost and time, ensuring that vital information is accessible to a global audience and enhancing the organisation's ability to collaborate effectively across diverse regions.

But how?

Whisper AI has dramatically increased the quality of speech recognition of audio-to-text.

Tech giants Meta, Amazon and Mozilla have all made translation advances, including under-represented languages, which are becoming productized.Virtual Assistants: ChatGPT can reduce staff workload, by summarising meeting notes, triaging emails, and creating intelligent alerts that connect new information with the current priorities of staff.

But how?

Enabling tools like LangChain are making it possible to string multiple actions together, and AutoGPT is making it possible for Chatgpt to prompt itself to come up with and execute a plan of action. These are resulting in first assistants like Milo, an assistant for busy parents.

What are the risks?

With any technology, there are risks that need to be assessed and with ChatGPT, those risks could be more than most. The Outsight Team can help you navigate these in the way that ensures it’s possible to improve efficiency without taking unacceptable risks. Some of the common risks associated with the use of ChatGPT are as follows:

Organisational Misinformation: The potential for ChatGPT to provide inaccurate information is a risk that organisations need to consider. It is important to ensure that the data fed into ChatGPT is accurate and reliable, and that the model is regularly updated and retrained to reflect changes in the data.

Inherent Bias: ChatGPT may inadvertently reinforce existing biases in the data it is trained on. It is important to ensure that the data fed into the model is diverse and representative.

Privacy Risks: ChatGPT has access to sensitive information and needs to be trained with data that respects the privacy of individuals. It is important to establish clear policies and procedures to protect the privacy of individuals.

Legal Risks: The use of ChatGPT needs to comply with the relevant laws and regulations, including data protection laws.

Reputational Risks: If ChatGPT is used to produce content or communicate with stakeholders, there is a risk that the communication may not reflect the values and tone of the organization, potentially leading to reputational damage.

How Outsight can help

To ensure safe and effective adoption, we must map the optimal use cases for the organisational level, and empower bottom-up understanding and best practices at the individual level. Outsight can support and accompany organisations on their journey to leverage this game-changing technology, and has developed a stepwise program, including:

Mapping use cases relevant to the organisation's operations.

Evaluating the limitations and risks associated with the identified use cases, along with a generalised framework.

Prioritising innovation opportunities based on short, medium, and long-term impact.

Developing education and capacity building content, workshops and trainings to have a repeatable and scalable impact on the safe adoption of ChatGPT from an end-user perspective..

Supporting the implementation of capacity building programs to take advantage of cost and time savings effectively.

The ultimate goal is to support organisations to take up the dramatic time and cost-saving opportunities made possible by this technology, while protecting against the risks and limitations amidst the hype.

ABOUT the author and OUTSIGHT INTERNATIONAL

Harry Wilson

Harry is a product person and consultant on applying technology for impact. He has led teams which have built products used by the WHO, World Bank, UNICEF, Inter-American Development Bank, as well as acted as a consultant to companies like Facebook for Good, Microsoft and Intel. His specialist areas are AI & data, blockchain and communities.

ChatGPT

ChatGPT is a sophisticated language model powered by OpenAI's state-of-the-art GPT-3.5 architecture. With a vast knowledge base spanning a wide range of topics, ChatGPT is an expert in answering questions and generating natural language responses that are both informative and engaging.

Outsight International

Outsight International provides services to the humanitarian and development sector in an efficient and agile way. Outsight International builds on the range of expertise offered by a network of Associates in order to deliver quality results adapted to the specific tasks at hand. If you’d like to discuss working with the Outsight team, please get in touch or follow us on LinkedIn for regular updates.